Solving Australia’s Labour Shortage by Taking a Hard Look at Ourselves

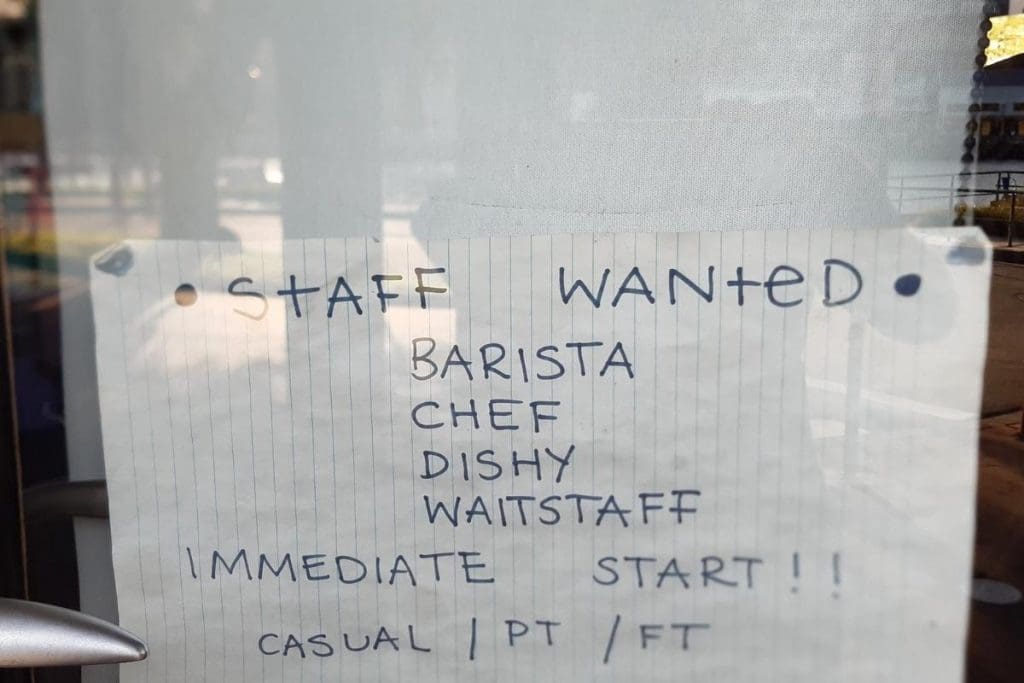

News and headlines over the past two years have told us again and again that a severe labour shortage exists in Australia across multiple industries from hospitality to child care, logistics to agriculture.

Prior to Covid-19, this gap was mostly filled by Working Holiday Makers and international students, living in Australia on temporary visas. Border closures stopped the flow of these visa holders and jobs usually filled by these workers – night fillers, care workers, fruit harvesters, food trade workers, warehouse workers1– have remained vacant.

How did we arrive at such a heavy reliance on international labour, and why aren’t Aussies filling these jobs?

It is not an easy conundrum to solve as there are multiple contributing factors.

Is one of those factors Australia’s very own history?

Australia’s Work Ethic: A Potted History

The Aussie Battler

The Aussie Battler was born out of the 1890s depression but gained prominence in the Great Depression of almost a century ago, and has been part of the national jargon ever since.

The Aussie battler displays that ‘great Australian virtue’ of being able to improvise and make do and was a person who ‘struggled to survive … and who wouldn’t give up.’2

Have we lost that ability to ‘make do and mend’, to suffer through hardship, do what it takes? Have we retreated into a comfort zone from which we are not willing to leave?

Is the Aussie battler merely a myth?

The Lucky Country

Australia’s history shows that we Australians have suffered few real, continuing, national hardships.

With no land borders, Australia suffers neither from border incursions nor threats of war. We have never had hostile troops on our soil. We have a stable democracy and system of government. We have an environment that allows us to harvest and produce sufficient food to feed the nation; we do not have to queue in breadlines or use food coupons for basic necessities. And, while we regularly suffer at the hands of nature – drought, fires, floods, even so we do not suffer widespread famine or homelessness.

World War II caused hardship and suffering for Australia and Australians; however, in its wake, opportunities arose. Women became a permanent part of the workforce, manufacturing revved up, increased migration and general economic activity allowed us to build the nation and participate in international trade. Our standard of living improved in step with advancements in materials and technologies.

As Donald Horne coined it in the title of his 1964 satire, we became ‘the Lucky Country’.

Horne used the term ironically, arguing that Australia’s economic prosperity was largely derived from its rich natural resources and immigration. Horne observed that Australia “showed less enterprise than almost any other prosperous industrial society.” Australia consisted of a ‘lazy derivative society lacking innovation and enterprise. ‘Australians were simply riding to prosperity on the sheep’s back, enjoying their country’s natural advantages in the wool industry.’3

Scathing commentary!

But is it, in fact, true?

When we look at the swathe of jobs that have been going begging since Covid-19, it seems that, even in the greatest pandemic of all time, our social welfare system offers some unemployed Australians a preferable alternative to going the hard yards and taking up those roles.

Especially when we have a history of reliance on a workforce of temporary visa holders.

Labour Supply (Visa) Programmes

‘Luckily’, Australian governments have created a range of visa programmes that help fill shortfalls in our domestic labour market. And provide a lucky break for those who dream of moving Down Under, to the land of opportunity.

Programmes such as the Working Holiday and Work & Holiday visa schemes, Student visas, Training visas and others, provide a red carpet for a willing workforce.

Pre-pandemic, as at 31 December 2019, there were 119 817 Working Holiday visa holders, 480 543 Student visa holders (this number includes both the main student and family unit members) and 89 324 Skilled Graduate visa holders 5 in the country.

These three programmes alone provide a substantial potential workforce of almost 700 000!

So, how ‘available’ is this workforce?

Working Holiday Makers are restricted to working six months on each visa for any one employer. International students (except some Master / PhD candidates) are restricted to working 40 hours per fortnight (although, ‘generously’, this has recently been extended to full time work to allow students to assist in addressing Covid-19 work shortages).

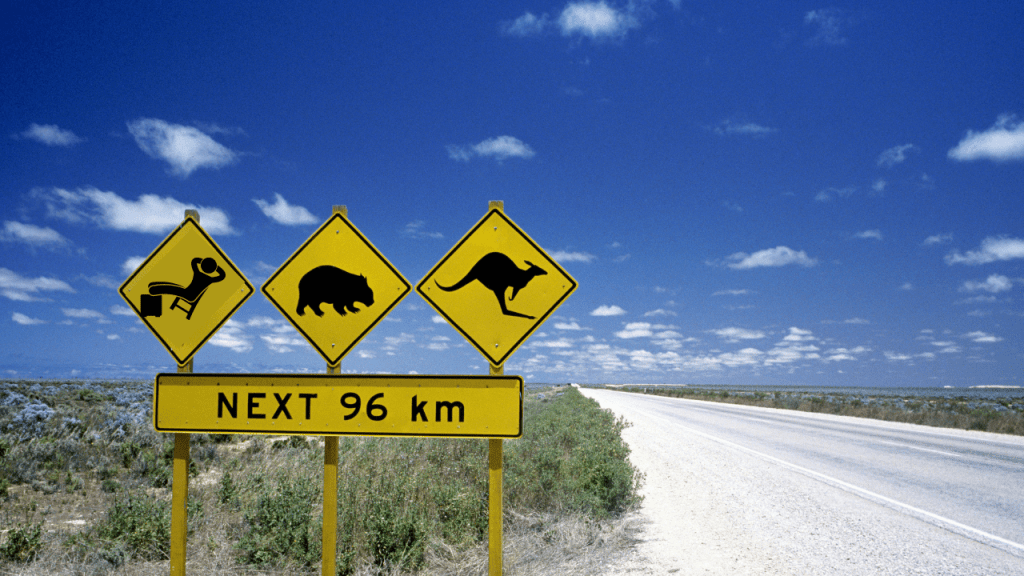

Working Holiday Makers may extend their visas for a further year if they work for three months in regional areas undertaking work ranging from plant and animal cultivation to mining, tree farming, fishing and pearling, construction and, in ‘very remote Australia’, tourism and hospitality work.

There are, however, no designated pathways for either the Student or Working Holiday visa holders to remain permanently in Australia. Of course, they can access other migration pathways if eligible, such as via Partner, Skilled or Employer Sponsored routes. But there is no visa offered to them purely on the basis that they are undertaking work that Aussies opt not to do.

And then we have the Pacific Australia Labour Mobility (PALM) scheme, which allows eligible Australian businesses to recruit workers from nine Pacific islands and Timor-Leste for seasonal jobs when there are labour gaps in rural and regional Australia.

Generously, the PALM ‘allows Pacific and Timorese workers to take up jobs in Australia, develop their skills and send income home to support their families and communities.’ (How exactly is this different from the now widely condemned use of Kanakas in Queensland’s sugar cane plantations in the 18th & early 19th centuries?)

We rely on this temporary and fleeting workforce to fill jobs which are often physical in nature, require long working hours or are regionally located. And then, without a by-your-leave or thank you, we show them the door.

Sponsorship Options for Aussie Employers

Australian business owners – large and small – employing such temporary visa holders spend time, effort and money in recruiting, training and employing these temporary workers. Again. And again. And again.

Understandably, many wish to break this cycle by retaining these willing workers on a longer term basis by accessing employer sponsorship programmes.

The Medium and Long Term Skills Shortage List (MLTSSL) specifies occupations in which employers may nominate visa holders for a four-year visa, with a pathway to permanent residence after three years. Occupations here include chef, engineers, some ICT professionals, construction trades.

Employers can access additional occupations falling within the Short Term Skilled Occupations List (STSOL). Think Marketing Specialist, Laboratory Manager, Journalist. Visas for these occupations are available for two years, renewable twice, but with no pathway to permanent residence. Unless the position is regionally based.

And, reserved for regional areas, you will find occupations on the Regional Occupations List (ROL) such as HR Advisor, Dentist, Retail Manager, First Aid Trainer.

But even given the numerous occupations available on these lists, employers often come up against a brick wall in that the positions they wish to fill are not available for sponsorship.

You won’t find barista, fruit picker, aged care worker, truck driver or service station attendant on any of the lists. Employers may only sponsor workers such as these through complicated programmes such as Labour Agreements and Designated Area Migration Agreements; programmes specifically developed to fill the recognized shortfall in the occupation lists!

So, there are some occupations which are apparently in high demand and can lead to permanent residence (PR) for the visa holder and a long-term worker for the employer.

Other occupations are available nationwide, but only for two-year stints.

Other occupations again are excluded from sponsorship in metro areas or are not available at all.

No wonder employers are confused!

It is difficult to rationalize to employers why, if their business were located two postcodes to the west or south, it would be able to sponsor a Construction Estimator, a Nursery person or a Vocational Teacher but due merely to geographic boundaries, they are not able to do so.

If we are to support all Australian businesses, then (surely?) we should provide all Australian businesses with equal opportunities to access international workers on a long-term basis?

Assuming there is no Australian available, of course.

Jobs for Aussies? Aussies for Jobs?

Both major political parties in Australia espouse ‘jobs for Aussies’.

Employers wishing to nominate workers on the MLTSSL, STSOL or ROL for temporary visas, must seek – via nationwide advertising over a period of a month – to find a suitable Aussie for the role first, and can only nominate where none is available.

This is often a ‘tick the box’ process to placate unions, when in fact employers already have a valuable international worker identified for the role.

Those who oppose the various ‘guest worker’ schemes claim that international workers are ‘taking Aussie jobs’.

Yes, these workers are taking Aussie jobs, but they are not taking Aussies’ jobs.

Why? Because unemployed Aussies are not taking up those jobs. Perhaps because they do not wish to relocate to where the jobs are, prefer not to undertake demanding physical work or long hours or do not wish to commit to a long-term position.

Employers complain time and again about their efforts to recruit and retain Australians across a range of industries and occupations. They claim that Aussies are unreliable or have little motivation and commitment to the job. On the other hand, the same employers extolled the virtues of existing ‘guest’ workers who are committed, flexible and hard-working. This cohort may have suffered hardship in their own countries such that they recognise the opportunity that working in Australia offers.

So, how can we reverse the tide of history and ‘make’ Aussies take these jobs?

Training and apprenticeship schemes are often touted as the be-all and end-all to the problem. And yet enrolments in such schemes are low. Commitment to a four-year study programme is not on the agenda for many. Attractive incentives would need to be created to overcome the lethargy when it comes to skilling and upskilling Aussies.

Should we recognize, at last, that these programmes do not work, do not fill the growing labour shortage gaps? And, if Aussies are ‘unavailable’ for the jobs, why not plug the gaps – permanently – through a consistent national migration programme?

Redefining our Migration Paradigm

Australia, it seems, wants to be seen as a country of innovation and skills.

Australia’s migration policy seeks to attract the world’s best and brightest for programmes such as the Global Talent initiative, the General Skilled Migration programme and the Employer Nomination Scheme.

Why are we fixated on only bringing in workers in a limited range of occupations? Why are more lowly skilled jobs / workers considered less valuable? Does a supermarket shelf stacker have less value to society than a FinTech specialist?

The recent shortage of workers in ‘critical sectors’ such as retail, food production, supply chain, aged care and agriculture, has proven beyond doubt that these workers are essential to the very functioning of our society.

So, if we do value them, should we not ‘thank’ them with the opportunity to continue to live and work in Australia?

Reliance on Working Holiday makers, students and Pacific Islanders is a temporary fix. It does not resolve the long-term problem.

That can be resolved both by encouraging, motivating, training Australians to take those jobs, and by providing pathways for migrant workers to remain in Australia long term.

Perhaps it’s time to get off our high horse when it comes to our migration mentality and it’s time to take a realistic look at who we would need in our community.

Let’s not merely invite workers to come temporarily and slave away at the difficult jobs, let’s offer them the opportunity to make a life in this country.

We can all reap the rewards.

For over 25 years, Sarah Gillis and her team at Aspire Australia have been helping clients realise their dreams of migrating to Australia. If you are wanting to start a new life in Australia, please contact us today.

- (Vacancy Report, December 2021, National Skills Commission, January 2022 https://lmip.gov.au/default.aspx?LMIP/GainInsights/VacancyReport

- https://www.macquariedictionary.com.au/blog/article/104/

- Contemporary Australia: 6. The Lucky Country, Sara Cousins, Monash University National Centre for Australian Studies, 2005

- (Working Holiday Maker visa program Report: 31 December 2019, Department of Home Affairs),

- (Student visa and Temporary Graduate visa program report at 31 December 2019, Department of Home Affairs.)